Nigeria’s Backward Culture of Treating Symptoms, Ignoring Causes: The Burden of Proof Debate as a Mirror of Systemic Electoral Dysfunction

By Sylvester Udemezue

INTRODUCTION

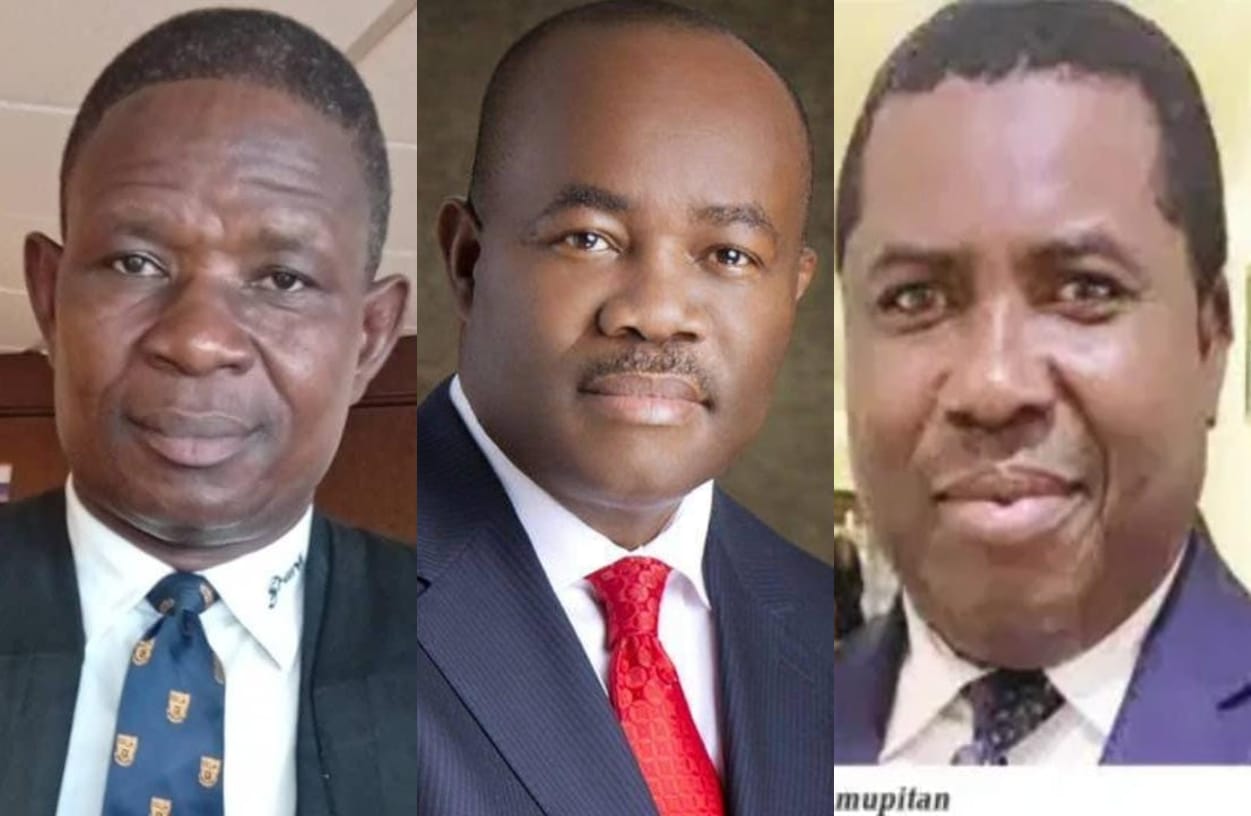

The Nigerian Senate is considering a proposal to amend the Electoral Act by shifting the burden of proof in election petitions from aggrieved candidates to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). Currently, under the Evidence Act, the petitioner must prove that electoral irregularities occurred, but Senate President Godswill Akpabio and Senator Seriake Dickson argue that since INEC is responsible for organizing, supervising, and conducting elections, including collation and logistics, it should bear the responsibility of proving that the process was free, fair, and lawful. The proposed reform aims to enhance credibility, transparency, and accountability in the electoral process. The bill also seeks to transfer local government election oversight from state electoral commissions to INEC, make the Permanent Voter Card (PVC) optional for accreditation, and strengthen the use of technology and real-time result transmission. Having passed its second reading with little opposition, Senate leaders plan to conclude the amendment process before December 2025 to ensure implementation ahead of the 2027 general elections. Analysts describe the proposed shift of the burden of proof as one of the most far-reaching electoral justice reforms since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999. (Source: Punch, “Electoral Act: Senate proposes shifting election proof burden to INEC,” 22 Oct 2025).

However, highly respectable and widely respected legal luminary and a former President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), Joseph Daudu, SAN, Life Bencher, has urged the Senate not to tamper with the existing burden of proof in election petitions, insisting that it should remain with the petitioner (the challenger) to prove alleged electoral irregularities. He warns that shifting this burden to INEC, as proposed in the 2025 Electoral Bill, would distort longstanding principles of justice and fairness and could weaken accountability in electoral adjudication. (Source: NAN, “2025 Electoral Bill: Don’t tamper with burden of proof, Daudu urges,” 26 Oct 2025)

Truth is, for many years, stakeholders in Nigeria’s elections have lamented perceived manipulation of results because result-management remained essentially manual, producing weaknesses that fuel post-election petitions and rancour. The Electoral Act 2022 attempted to legitimise e-management of results, but Nigerian courts in 2023 held that electronic transmission was not an indispensable requirement. Since then there has been renewed agitation to make electronic transmission mandatory. This article argues that the recurring contest over the burden of proof in election petitions is symptomatic of a failed electoral system: one that tolerates discretion, creates opportunities for manipulation, and therefore forces litigative after-the-fact remedies. It offers recommendations on how best to make Nigeria’s election result-management impregnable to manipulation through mandatory, non-discretionary electronic transmission and related safeguards.

LEARNING FROM ADVANCED DEMOCRACIES AND STABLE AFRICAN SYSTEMS

The recurring disputes in Nigeria stand in stark contrast with elections in other jurisdictions. The United States held its presidential election in December 2024, and the United Kingdom conducted its general election earlier the same year, producing Sir Keir Starmer as Prime Minister. Remarkably, both elections concluded smoothly; no major election petitions, no protracted courtroom battles. Similarly, in South Africa and Ghana, recent presidential elections were conducted without a single serious post-election dispute. In each of these jurisdictions, the outcomes were broadly accepted by the electorate, reflecting strong institutional credibility, procedural transparency, and public confidence in the electoral process. These examples demonstrate a critical truth: where the electoral system is strong, litigation becomes unnecessary. When rules are clear, processes are fair, and results are credible, there is little incentive for losers to seek justice through the courts. As Justice Louis Brandeis of the U.S. Supreme Court once observed, “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.” Transparency, not litigation, is the real guarantor of legitimacy.

By way of contrast, Nigeria’s electoral landscape has been characterized by what can be termed a culture of post-election adjudication. Virtually every major election triggers a flood of petitions and appeals: a pattern that suggests not the vibrancy of democracy but the weakness of its foundations. When disputes become the rule rather than the exception, it signals systemic malfunction. As Prof. Attahiru Jega, former Chairman of INEC, once lamented, “An electoral system that depends on the judiciary to determine winners is fundamentally flawed.” The courts should be the last resort, not the centre stage, of electoral legitimacy. The lesson is clear: preventive safeguards (such as transparent collation, reliable voter identification, electronic transmission of results, and impartial oversight) reduce the causes of disputes. Strong institutions, not strong men, ensure electoral integrity. Public confidence grows not through judicial pronouncements, but through visible fairness and procedural predictability. As Kofi Annan Once said, “Elections are not just about who wins, but about the process by which the will of the people is expressed and respected.” Until Nigeria’s electoral reforms move from treating the symptoms (litigating over outcomes) to curing the causes (preventing malpractice), the courts will continue to bear the burden of political failure. Genuine reform must therefore focus on building impregnable electoral safeguards, not merely refining post-election litigation procedures.

THE PARADOX OF PROVING WHAT SHOULD BE SELF-EVIDENT

The renewed parliamentary row over who should carry the burden of proof in election petitions (the aggrieved petitioner or INEC) reveals a deeper pathology: an electoral architecture that routinely produces contestable results. If the administration and management of elections were transparent, auditable, and resistant to manipulation, there would be no need for a tensely litigated contest over evidential burdens. That the polity must debate shifting the burden of proof away from petitioners to the very institution that runs elections is an indictment of an electoral ecosystem that invites litigation rather than foreclosing it.

ELECTION PETITIONS ARE SYMPTOMATIC OF A FAILED SYSTEM, NOT ESSENTIAL

Election petitions are remedial instruments designed to address defects in the process and results. They are not, and should not become, necessary adjuncts of democratic expression. When elections reliably reflect the will of the people because processes are automated, auditable, and insulated from discretionary human intervention, petitions become rare anomalies rather than routine recourse. Thus, the prominence of petitions in Nigeria’s post-electoral life signals structural failures in the design and administration of elections.

BURDEN OF PROOF: A DEBATE THAT FLOWS FROM FAILURE

Under ordinary evidential rules, the challenger bears the burden of proof. The clamour to transfer that burden to INEC stems from a perceived inability to obtain documentary, electronic, or chain-of-custody evidence from a manager whose operations are opaque or discretionary. Rather than treat burden-shifting as the primary reform, the more fundamental fix is to eliminate the very conditions that make petitioners depend on proof that is hard (or impossible) to obtain. In other words, the debate over burden allocation is a second-order symptom; the first-order disease is an electoral system that permits manipulation, discretion, and unverifiable processes.

PLANNING FOR FAILURE: A POLITICS OF LOW EXPECTATIONS

It is telling that reform conversations often begin by designing litigation solutions rather than preventative systems. This is planning for failure: drafting mechanisms to manage the aftermath rather than to prevent the harm. Such an approach institutionalizes adversarial politics: participants focus on designing legal workarounds for foreseeable manipulations instead of investing in infrastructural and legal measures that remove manipulation’s preconditions. The better public policy stance is prevention: make elections so credible, transparent, and robust that litigation becomes unattractive, rare, and usually unnecessary.

MAKING ELECTION PETITIONS UNATTRACTIVE: THE REFORM OBJECTIVE

If the goal of democratic engineering is to reduce post-electoral instability and the incidence of petitions, reforms should make petitions unattractive by ensuring the electoral process is transparent, credible, and practically resistant to manipulation. This requires a twin strategy: legislative impregnable design (hard legal constraints that eliminate or sharply narrow discretion) and technological hardening (mandatory, tamper-resistant electronic processes with immutable audit trails). Only when both pillars are in place will litigation cease to be the default corrective.

TECHNOLOGY IS NECESSARY BUT MUST BE MADE NON-DISCRETIONARY

Technology alone is not a panacea. Its effectiveness depends on how the law constrains human discretion over its deployment, operation, and evidentiary status. The legislature must therefore mandate specific technological steps and make any departure from them automatically fatal to the affected result. Discretion, exceptions, and “may”-style clauses must be removed. Instead, “shall” obligations, mandatory nullification clauses for material default, and statutory chain-of-custody and audit requirements must be enacted.

PRINCIPLES FOR AN IMPREGNABLE ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION REGIME

(1). Mandatory Deployment: Electronic transmission of results from polling units to collation centres and national servers must be mandatory for all elections and stages. Any failure triggers automatic nullification and mandated reruns.

(2). No Discretionary Exceptions: The law must disallow subjective discretion by INEC officials. Any exception must be narrowly circumscribed, objectively verifiable, and require pre-existing, publicly available contingency protocols.

(3). Immutable Audit Trail: Every electronic transmission must produce a time-stamped, immutable digital record retained in multiple independent repositories.

(4). Mandatory Real-Time Publication: Results as transmitted must be published in real-time on an official, publicly accessible portal, with metadata attached.

(5). Device and Software Certification: All hardware and software used must be certified by an independent technical standards body, with publicly documented, periodically renewed certification.

(6). Chain of Custody and Access Rules: The law must create clear chain-of-custody protocols and specify evidentiary weight of electronic logs.

(7). Independent Audit and Verification: Accredited auditors should run parallel verification checks during elections, with reports published within statutory timelines.

(8). Sanctions and Remedies: Material breaches trigger immediate statutory remedies, and criminal penalties should be available for deliberate tampering.

ANTICIPATING OBJECTIONS AND PRACTICALITIES

Opponents may argue that mandatory electronic regimes are vulnerable to technical failure, cyber attacks, or infrastructural constraints. These objections are manageable: the law must require objective, technical contingency plans and robust cybersecurity standards. Such mechanisms must be prescriptive, transparent, and limited: not broad discretionary powers that can be abused.

WHY DEBATE ON BURDEN-SHIFTING IS THE WRONG FOCAL POINT

Shifting the burden of proof to INEC treats symptoms, not causes. It presumes the possibility of obtaining trustworthy evidence from the election manager; in contexts where managers exercise wide discretion and results are opaque, a legal shift may produce political backlash, reduce incentives for technological reform, and create perverse incentives for both INEC and litigants. A better path is to make the evidentiary record self-generating and self-verifiable through mandatory technical and legal safeguards, rendering burden disputes largely academic.

CONCLUSION: FROM LITIGATION CULTURE TO IMPREGNABLE PREVENTATIVE DESIGNS

The recurring debate over who must prove electoral irregularities mirrors the system’s structural weaknesses. If Nigeria’s goal is durable democratic stability, reforms must make litigation the exception, not the rule. The National Assembly can and should legislate an impregnable electronic transmission and result-management regime that eliminates discretion, creates immutable audit trails, mandates real-time public disclosure, and prescribes automatic remedies for non-compliance. Such reforms will not only reduce the incidence of petitions but strengthen public trust and the legitimacy of governance itself.

SELECTED FURTHER READING & REFERENCES

1. “Electoral Act: Senate proposes shifting election proof burden to INEC,” Punch; 22 Oct 2025.

2. “2025 Electoral Bill: Don’t tamper with burden of proof, Daudu urges,” NAN; 26 Oct 2025.

3. “Amupitan, Nigeria’s electoral problem lies not in INEC chairman’s qualifications but in weak and manipulable laws.” By Sylvester Udemezue.

4. “How Nigeria’s National Assembly Can Make the Electoral System Impregnable on Electronic Transmission to Prevent Fraud During Election Result Collation”, By Sylvester Udemezue: IJPLD (2025).

5. “Adodo’s Alarm over Governor Aiyedatiwa’s Alleged Disrespect for the Constitution” By Sylvester Udemezue (Law & Society Magazine, 20 May 2025).

6. “Rethinking System Change in Nigeria: Why Only Impregnable Legal Reforms Can Deliver Real Impact” By Sylvester Udemezue (20 May 2025).

Respectfully,

Sylvester Udemezue (udems)

Proctor, The Reality Ministry of Truth, Law and Justice (TRM)

TEL: 08021365545. udems@therealityministry.ngo.

WEB: www.therealityministry.ngo.

(27 October 2025)